Chair of our roundtable series and former NHS Confederation Chief Executive, Mike Farrar, shares his key takeaways from the conversation to inform our understanding of international best practice for improving emergency care.

Across the globe, countries are still feeling the strain on healthcare systems brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic. Many people were denied treatment due to COVID-19 delays, and now there have been big political pledges to get people back into care and reduce waiting times.

Our ability to improve care delivery must first focus on managing urgent and emergency care. This way, we can ensure that we are best utilizing hospital capacity and staff to bring in people for planned treatment. Unless we get our emergency care system right, we are going to continue losing capacity day in and day out.

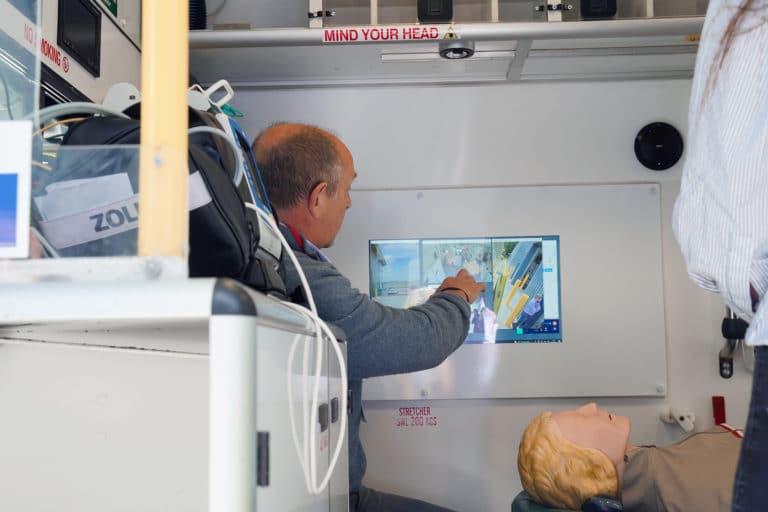

Our focus must therefore turn to the way in which we provide these services. There is a terrific opportunity to use technology, such as the application of digital innovations, to improving emergency care.